Cutting Room Jams: Greg "Ironman" Tate

Michael Gonzales helps introduce a collection of the late writer's work for Musician magazine.

Earlier this spring, I picked up a collection of back issues of Musician magazine from a person I found on Craigslist. Musician was a favorite of mine growing up and the person, who lived in San Rafael, gave them away for free. Most of the issues were published in the early 80s and included cover stories on Prince, Miles Davis, Joni Mitchell and others.

Fast forward to October 16, when I caught a post by Michael Gonzales on Twitter/X celebrating the late Greg Tate’s birthday.

Tate, who passed away on December 7, 2021, was a major Black cultural critic and musician who wrote for the Village Voice and other publications from the early 80s onward. His 1992 collection of essays, Flyboy in the Buttermilk, is considered a foundational work by critics and journalists, including myself. He’s also remembered for co-founding the Black Rock Coalition, an advocacy group that promotes Black musicians’ and combats racial stereotypes and industry segregation affecting their work.

As a protégé of Tate, Gonzales is esteemed in his own right. In 1991, he published a collection of hip-hop criticism, Bring the Noise, with then-Billboard columnist Havelock Nelson. Some of his more notable pieces include The Source’s five-mic review of the Notorious B.I.G.’s posthumous second album, Life After Death. Today, he’s a memoirist who writes about New York culture as well as a short-story writer and critic who explores crime films and Black literature.

When I responded to Gonzales’ post that I found a handful of Tate articles in Musician magazine that I couldn’t find online, he asked me to post them. I refuse to contribute original content to Twitter/X any longer for obvious reasons, so I have posted them here.

To introduce these pieces, I asked Gonzales a few questions about why Tate has inspired generations of writers. Generously, he agreed to answer them. His responses are below.

Why is Tate so revered by music journalists? I’ve tried to explain in my newsletter, but perhaps someone who’s a direct descendant of his style can say it better.

Greg Tate began his writing life as a poet and fiction writer, a man who was as interested in style as he was in content. When he switched over to writing arts criticism he brought that bold style with him. As a young writer who was as excited by the comic book panels of Jack Kirby as he was by the paintings of Pablo Picasso, who was as inspired by the poetry (and liner notes) of LeRoi Jones as he was by the science fiction of Samuel R. Delany, he incorporated all of that into his work and the end result was quite exciting.

Writing for the Village Voice, an alternative paper that was respected across the country, Greg Tate wrote in a way that didn’t mask his Blackness nor nerdiness. When he wrote about P-Funk or electric Miles Davis, he never tried to shield who he was or what side of the colorline he represented. That said, he wasn’t close minded and could as easily write about other cultures as he could his own.

Personally, as a young Black nerd writer myself, it was wonderful to be introduced to the work of someone who was bold (unafraid) to be who he was while assuring others that they too can step into the light. Though there were a few Black writers at mainstream publications, they usually wrote in a “colorless” way that didn’t set them apart from their white counterparts. Greg Tate could have written like that too, but he didn’t want to. For young Black writers such as myself, especially those who got into arts writing, that was revolutionary.

Of course, Tate’s appeal as a writer wasn’t limited by race. His fanbase, like his writing, was expansive.

Can you describe Tate’s tastes, particularly to someone who only knows his writings on Black music in Village Voice and Vibe? As shown by these pieces, they’re very specific to music culture in the early 80s, and may be foreign to folks who grew up in rap’s golden era and beyond.

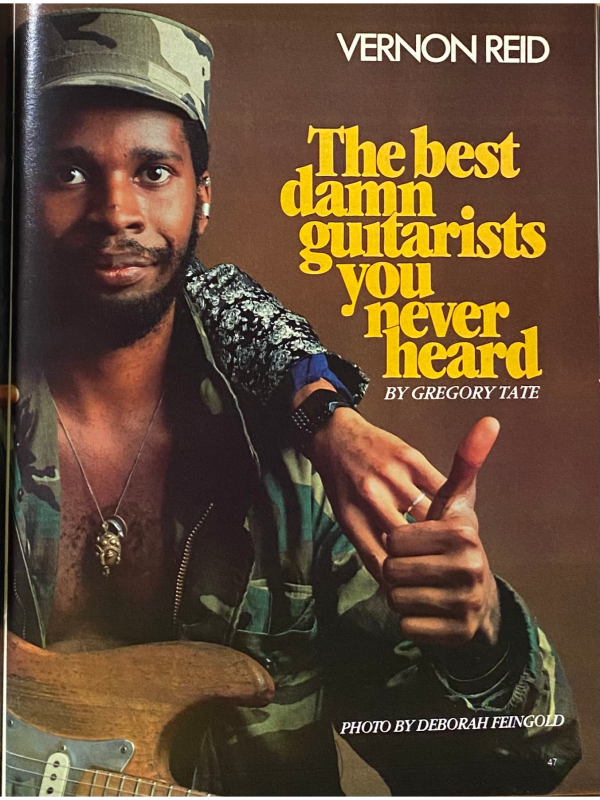

Part of what made Greg a brilliant writer and thinker was the fact that his taste was literally all over the map, or should I say globe. He was as interested in the music coming out of Brixton as he was about the beats emerging from the Bronx. He wrote about the (old) Afrobeat of Fela and the juju music of King Sunny Ade. As the co-founder of the Black Rock Coalition alongside his best friend Vernon Reid, he too loved that music no matter what color the musicians were…as long as they were dope.

Greg Tate didn’t just write about music, but also about books, art, and sexuality. He never limited himself or his writing.

Greg was also a musician, a guitarist who was also a conductor. In his music, he pulled from many sources, races and sexes. He was as inspired by Big Mama Thornton as he was by Jimmy Page. It was though Greg’s writing that my (and I’m sure many others) musical knowledge expanded. He turned me on to folks like Cecil Taylor, AR Kane, and Pete Cosey as well as numerous writers including Jack Womack, Don DeLillo, and William Gibson.

I want to ask you about the idea of hip-hop as a worldview. It’s something that people now associate with pop consumption — streetwear, stylized approaches to consumer objects like toys and cars, digital audio, and internet culture. But in the 80s, it was firmly rooted in funk. Tate’s work seems inspired by the latter, which is how he got from Jean-Michel Basquiat and Nona Hendryx/Material to David Byrne and Arto Lindsay. His approach reminds me of the work of early hip-hop innovators like Afrika Bambaataa (apologies for bringing up his name) and Grandmaster Flash. Correct me if I’m wrong.

I think in the early years of hip-hop, the music wasn’t limited. Of course James Brown, Sly Stone and George Clinton was used, but it wasn’t just that. Bam talks about playing and loving the Sex Pistols, the first time I saw Run-DMC was at Danceteria, a new wave club in NYC (where more than a few rappers performed) and the scene became a literal moveable feast with people like Fab Five Freddy and Michael Holman bringing the music to art galleries and alternative art spaces. Graffiti artists were as inspired by Andy Warhol and Vaughn Bode as anything else. Rap music, as Tate saw it, came out of the hood, but it didn’t have to just be pissy staircase soundtracks. Tate embraced De La Soul and PM Dawn.

You must realize, too, when you drop names like “David Byrne and Arto Lindsay,” those guys were a part of the same Lower East Side scene(s) as Tate, Vernon Reid, Melvin Gibbs, and other Black folks. They heard and loved “our” music as much as we were digging “theirs.” I’m sure Arto and Vernon were playing together, and Greg was right there in the mix. Nona Hendryx, who was an early member of the Black Rock Coalition, was also down with Bill Laswell and the Talking Heads.

For Greg Tate, Black culture was real, but it was also surreal; it was fearless, but not something to be afraid of. Black culture was bowties and doo-rags, caviar and chitlins.

Before we begin, here’s some pieces on Tate by Gonzales and others.

Ravers: The Black Arts Coalition Magazine, special edition 2022

“A Love from Outer Space: Why Greg Tate Matters,” Blackadelic Pop, October 25, 2007

“Fear of Music: A Tribute to Black Rock Coalition,” Red Bull Music Academy, October 7, 2015

“Afrodisiac: A Textual Meditation on Greg Tate,” Literary Hub, December 14, 2021

“Flying High: Remembering Greg Tate,” Village Voice, December 13, 2021

First, here’s a “Faces” profile on Golden Palominos from Musician, November 1982.

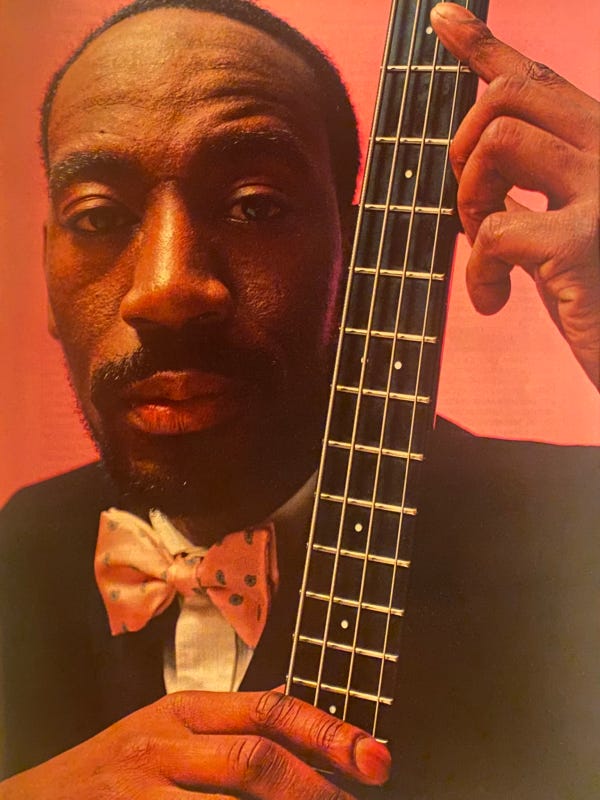

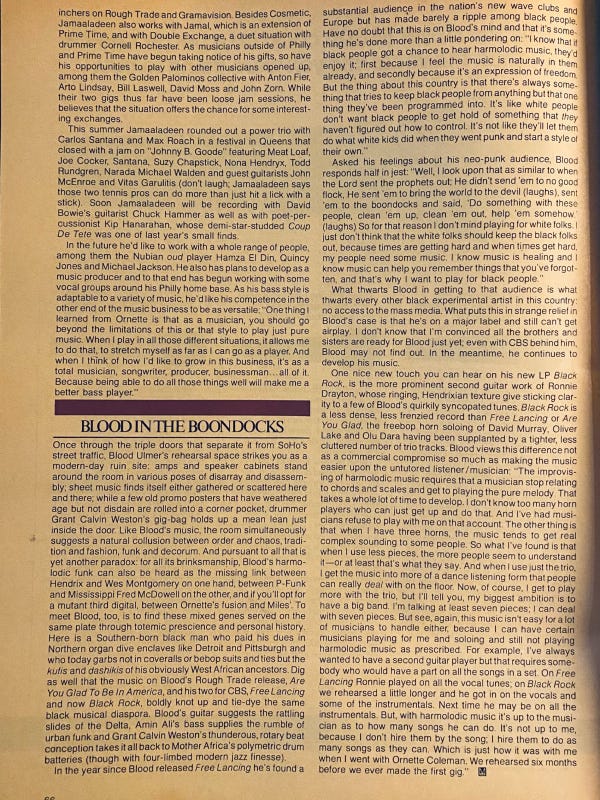

Here’s a feature on “The Sons of Ornette,” James Blood Ulmer and Jamaaladeen Tacuma, from Musician, January 1983.

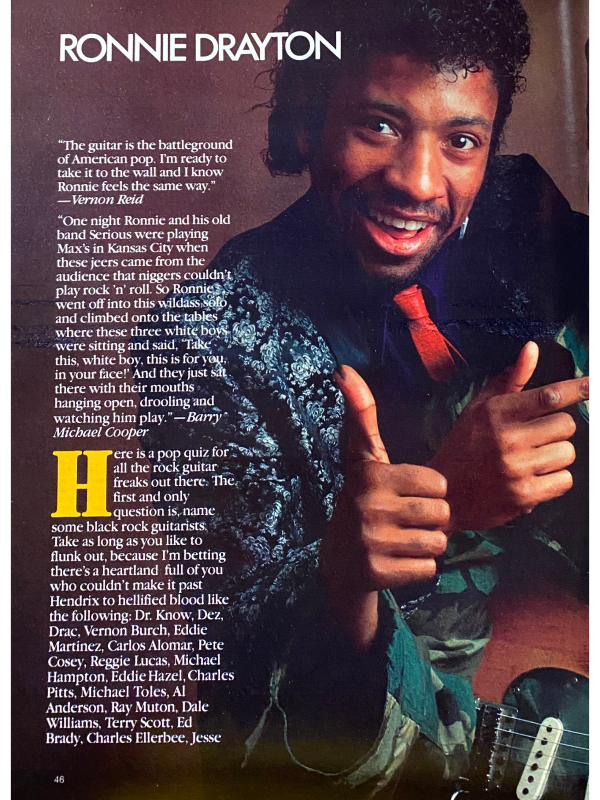

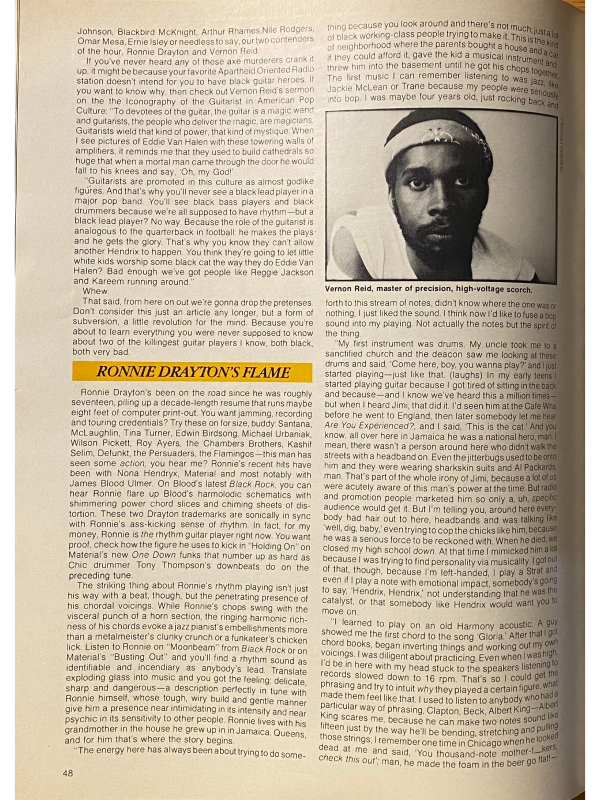

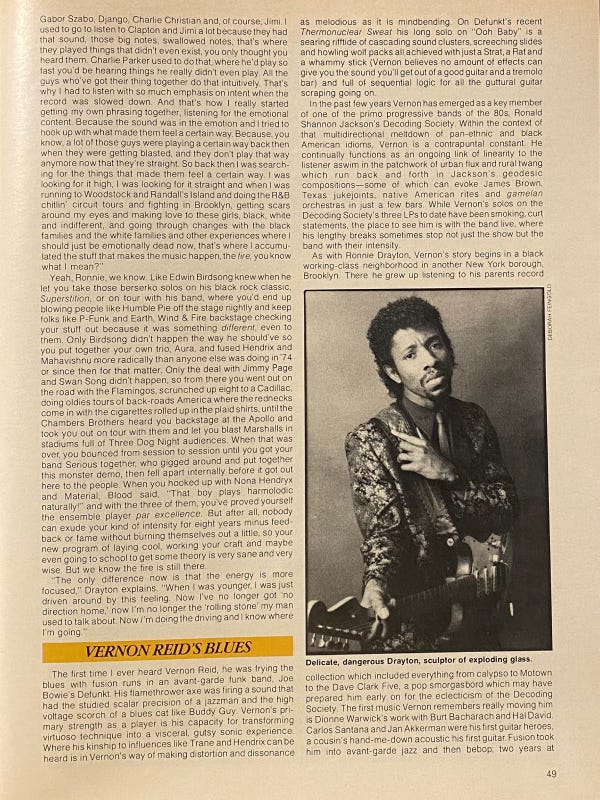

Here’s a feature on Ronnie Drayton and Vernon Reid, Musician, July 1983.

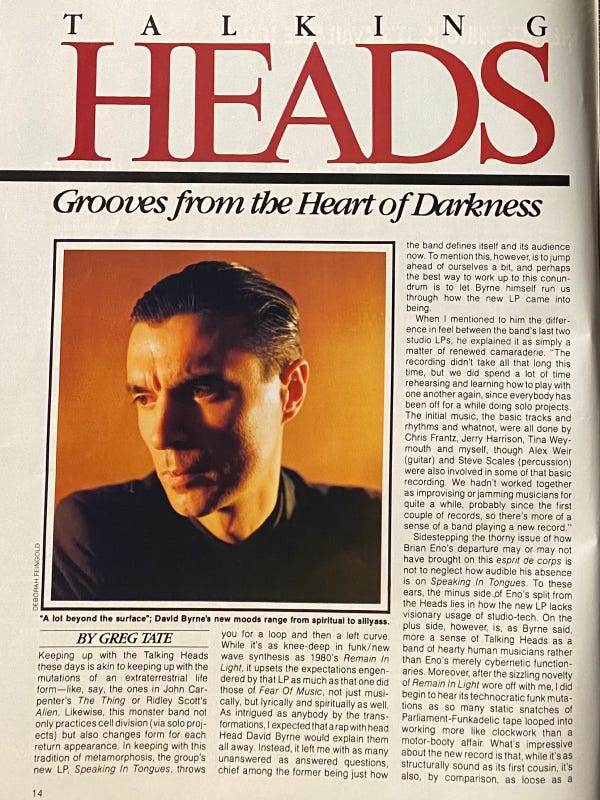

Here’s a feature on Talking Heads from Musician, September 1983.

Here’s a review of Nona Hendryx’s The Art of Defense, Musician, June 1984.

Finally, apologies for not discuss my own work these past few weeks. Yes, I have published a few things recently. I’ll get to those soon.