Cutting Room Jams: Underground Rap's Gender (Im)Balance

An essay originally published in The Wire, ELUCID in concert, and thoughts on Jean Grae's memoir.

In January, The Wire editor Lucy Thraves issued a call to contribute to an opinion-based section it once published until 2018, “Collateral Damage,” and is now reviving as “Against the Grain.” I sent her a premise I’ve thought about: where are the women in underground hip-hop?

In recent years, I’ve reflected on why I didn’t speak out about the absence of women in the so-called “backpacker” scene during its peak in the early Aughts. Like every well-meaning male critic, I tried to write about women whenever I could. I was conscious of how men often rendered them in Madonna/whore tropes, reduced them to sexual playthings, chastised them for being hoes; and celebrated them as faithful wifeys, mothers, and caretakers. But I didn’t question the structural nature of their absence.

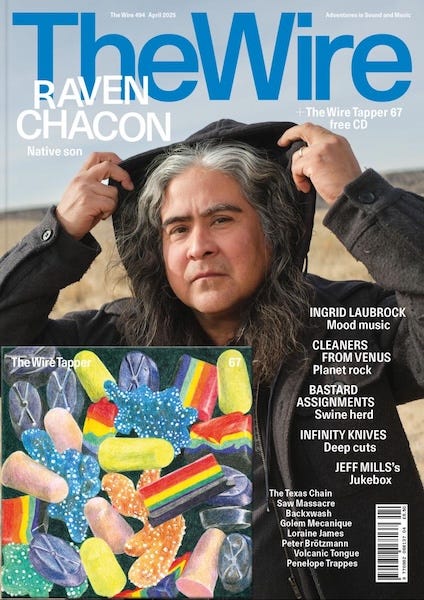

This essay, published in The Wire’s April 2025 issue, is my attempt to remedy that. Thanks to Thraves for the opportunity.

Against the Grain

Women set the tone in mainstream rap, but the underground hiphop scene lags far behind, argues Mosi Reeves

In 2025, mainstream rap is defined by a female voice stronger than at any time in the genre’s history. Even nostalgists for the mid-1990s, when giants such as Lauryn Hill, Lil’ Kim, Queen Latifah, Mia X and the late Gangsta Boo commanded attention, couldn’t have anticipated the way modern rap women shape the artform. They seem to multiply endlessly by the moment: Nicki Minaj, Cardi B, Megan Thee Stallion, Latto, Saweetie, Ice Spice, GloRilla, Sexyy Red, Flo Milli, Rico Nasty, City Girls (sadly, RIP).

Cumulatively, they feel like an overwhelming aesthetic force that anyone interested in rap must contend with. Despite ongoing popularity – this month, Doechii’s mixtape Alligator Bites Never Heal won the 2025 Grammy for Rap Album of the Year – they still feel like a provocation to what Megan Thee Stallion (real name Megan Jovon Ruth Pete) rightly called a “boys’ club” (she used this phrase during the 2022 trial and conviction of rap singer Tory Lanez, who shot her during an argument, then promulgated a cascade of misogynist vitriol against her when she pressed charges). Despite criticism over sometimes pornographic visual presentations and lyrical reductions of romance as fleeting and transactional, these artists effectively communicate to and for other women, relating everyday concerns that men don’t need to understand, much less sympathise with. In the process, they’re engendering a refreshing and much needed feminist transformation of hiphop culture.

Alas, a similar revolution hasn’t happened in underground rap. Hiphop is a complex sprawl of overlapping movements and heads will debate what exactly constitutes non-commercial rap. For now, let’s say it encompasses the kind of releases covered in The Wire. Its leaders, for the most part, are uniformly male.

Sceptics will note the presence of several women in the underground scene, like Nappy Nina, Maassai, Che Noir, Sa-Roc, Semiratruth and Backwood Sweetie. Moor Mother isn’t quite a rapper – she’s a vocalist who utilises incantations and sound art as well as rapped verse in her varied catalogue – but deserves inclusion on this list, thanks in part to her 2020 collaboration with billy woods, Brass. Noname, who has provoked and delighted with her thoughtful, humanistic lyrics about forging a life of Black activism, certainly qualifies as a leader. But she often appears as a sole female voice, the embodiment of the Hidden Figures meme in which pioneering Black NASA scientist Katherine Johnson (as played by Taraji P Henson) fights for recognition amid a room full of white men.

This isn’t the first time that the underground has escaped scrutiny over its patriarchal nature. Back in the 1990s and 2000s, when ‘indie rap’ self-righteously constituted itself as a less capitalistic and more innovative corollary to the blingy mainstream, few if any wondered why prominent labels like Rawkus, Definitive Jux, Stones Throw (before adding the iconoclastic Georgia Anne Muldrow in 2006), Rhymesayers, Duck Down and Anticon didn’t have women on their rosters. No one questioned why talented musicians like Medusa, Apani B and Stahhr The Femcee never elicited the industry attention they clearly deserved, or why T Love heartbreakingly burst into tears while discussing her career in Nobody Knows My Name, a haunting 1999 documentary about the pressures faced by women in hiphop. This era is searingly depicted by Psalm One, who secured a deal with Rhymesayers for her 2006 album The Death Of Frequent Flyer, in her 2022 autobiography Her Word Is Bond: Navigating Hip Hop And Relationships In A Culture Of Misogyny. “Most rappers will go their whole career without ever sharing a tour vehicle with a woman artist,” she writes, describing how alone she felt on her early tours. “I’ve never felt physically threatened by a man on tour, but I’ve never felt 100 per cent safe either. That’s a terrible reality lots of women artists endure on the road.” She adds that Rhymesayers treated her poorly after the release of Flyer, undermining her creative ideas and attempts to publicise her work, leading her to observe, “This label that was looked at as so progressive was anything but when it came to me.”

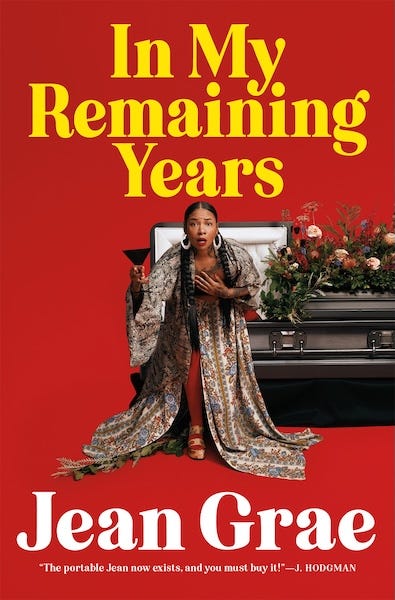

By contrast, Jean Grae’s new collection of autobiographical essays, In My Remaining Years, barely mentions her lauded three decade rap career at all, understandable given that the multidisciplinary artist has evolved into a humourist, playwright and visual artist who writes sharply and poignantly about gender fluidity and transitioning into a “gender transcendent” state of being. For those of us who celebrate backpack classics like “Negro League Baseball” and “How To Break Up With Your Girlfriend”, as well as full-length forays such as Jeanius with producer 9th Wonder and Everything’s Fine with Quelle Chris, it’s painful to see her distance herself from a culture she once dominated with her sharp, powerful words. Perhaps she has little patience for a past that, no matter how fruitful, is undoubtedly burdened by an experience of being constrained within all-encompassing male oppression. In a section where Jean Grae wittily muses about how we should honour her at her funeral, she commands, “Absolutely no rap music I have ever been involved with in any way, shape, or form should be played.”

In today’s mainstream, women in rap are “winning”, as Lil Baby put it. One can question the true intentions of rap imprints rushing to sign their own dripped out, high maintenance snap queen that can do numbers on socials and streaming services. One can also ask why women like Rapsody, Tierra Whack and Leikeli47 who decline to present themselves in glammy, revealing poses seem to garner fewer viral hits and attention from fans. Regardless, the industry is making space for women and building a more inclusive culture in the process, no matter the resulting problems and concerns. By contrast, underground scenes appear comparably deficient, with men too content to augment their recordings with soulful vocalists (and to be fair, producers like DJ Haram and KeiyaA) while avoiding strong female presences that can spit as hard as they can in the booth.

Let me make it plain now, without naming and shaming: your favourite underground labels need to make space for women. There’s no reason why these imprints that earn regular placement on critics’ best of lists shouldn’t have at least one rapper that identifies as female and/or non-binary, if not more. Underground rap as a structurally male endeavour must end.

Related: Recent Rap Albums by Women

Here’s five rap albums by women that I’ve enjoyed.

Backwood Sweetie, Burn One: This is a fun five-track EP of soulful cuts from an imaginative Maryland rapper who touts the benefits of good psychedelics and mind elevation. She’s not yet well known outside of Bandcamp/indie circles, but she seems destined to be. A key track is “Kaleidoscope,” a cut produced by August Fanon where she boasts, “I’m a leader, be deep thinkin’/With a chin stroke, with excitement the waves peak, gradually increasing crescendo.”

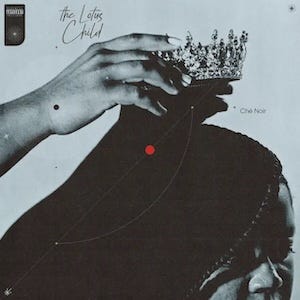

Che Noir, The Lotus Child: Buffalo, New York rapper Che Noir has issued quality projects for a few years now, including her 2020 collaboration with producer Apollo Brown, As God Intended. Still, her career seems stuck in a kind of netherworld, not grimy enough for a street rap scene defined by Westside Gunn’s Griselda imprint, but too sharp-elbowed for the backpackers. The best track on The Lotus Child EP, “Black Girl,” is a duet with Rapsody that addresses how hard-spitting women are too often marginalized.

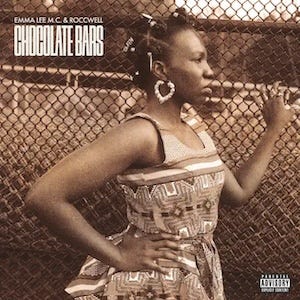

Emma Lee M.C. & Roccwell, Chocolate Bars: Emma Lee M.C. is a Harlem rapper with a studiously throwback style. On “Like It’s ‘93,” she throws out references to golden-era heroes like De La Soul and Black Moon while guest Masta Ace rues how the genre has been “ruined” by commercialization. Another cut, “Cravings & Withdrawals,” evokes the lovelorn crooning of D’Angelo’s “Jonz in My Bonz” amid an appearance from Bahamadia. But the cut I return to is “HHLU2 (Hip-Hop Loves You Too),” an optimistic dedication to the “women, girls, and dope femmes” that’s reminiscent of Rapsody’s early work with 9th Wonder. Chocolate Bars is produced by German beatmaker Roccwell.

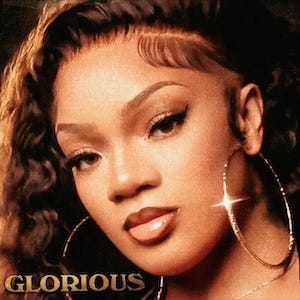

GloRilla, Glorious: When I reviewed Glorious for Rolling Stone last October, I found fault with how its fifteen tracks felt “truncated, snipped into quick two-verse, two-and-half-minute bursts to capture internet-addled attention spans.” Quibbles aside, it’s an entertaining debut from the Memphis rapper who’s logged several viral hits in the past several months. A key cut here is “I Ain’t Going,” where she pushes back hard against the threat of gender violence: “I ain’t going for all that rough-me-up and grab me by the neck/Nigga put his hands on me, we gon’ be smoking on him next.”

Nappy Nina & Swarvy, Nothing Is My Favorite Thing: Oakland-to-Brooklyn rapper Nappy Nina insistently questions life – her choices, the situations she finds herself in, the world around her – in a soft yet vigorous tone. Her unique cadence has carried her through several projects she’s released on her own label, LucidHaus, including this 40-minute album with Los Angeles producer Swarvy. When she raps on “Quickness,” “Choose knowing over being known/Dilapated hometown grown/Type of homophones and zones/I be in on my own,” it’s as if she’s chopping up her thoughts while she delivers statements of purpose.

ELUCID’s Revelator Tour

After I posted my Wire essay on my Instagram Stories, ELUCID invited me to his March 22 show at Neck of the Woods in San Francisco, a stop on a tour for his critically acclaimed 2024 album, Revelator.

I haven’t been to a rap concert in several months, and it clearly showed. First, I misjudged a step and fell flat on my face. As I just burst out laughing, the bartender asked if I was okay, then took pity on me and gave me a free beer. Later, I bought a cassette from ELUCID, only to set it down somewhere and misplace it – something I can’t remember ever doing before.

While I publicly humiliated myself, I took in local rapper Ace Diego, who rapped over an instrumental from Raekwon’s “Verbal Intercourse,” then led the room in a pair of chants, “Say spread love!” and “Say fuck Nazis!” He was followed by Mophono, who mixed a live set of dub, beat loops, and bass-y rap classics like Too $hort’s “Freaky Tales” and Original Concept’s “Knowledge Me.” Somehow, I missed Mars Kumari, who has earned buzz through her releases for Dalek’s Deadverse label and Danny Brown’s Bruiser Brigade imprint.

Then, Nappy Nina performed several tracks from her catalog, with producer Swarvy backing her. On wax, her stream-of-consciousness style of writing tends to sound quietly interrogative. But on stage, she delivers those lyrics with real passion, lending the music a pulsing quality that made her musings more communal and less introspective.

I was pleasantly surprised by the evolution of M. Sayyid, a rapper best known for his on-again, off-again membership in Anti-Pop Consortium, one of the most important abstract/experimental groups in rap history. In APC, Sayyid was a lyrical sniper who deployed his deadpan delivery to excellent effect. But his solo material, much of which can be heard on the Error Tape series, is markedly different. He sounds emotionally charged and eager to reveal himself. Initially, I found the contrast between his old, enigmatic APC guise and his new persona difficult to process. His rendition of the a cappella track “Quarterback (Freestyle),” finally helped me understand his new direction.

This night marked the second time I’ve seen ELUCID in concert. Previously, I saw him with Armand Hammer, his supergroup with billy woods, when they played at New Parish in 2023. While that show coasted on the pair’s affinity for grungy alt-rap dynamics and crowd-pleasing punchlines, ELUCID’s solo performance proved a more intense experience. The way he punctuates his verses with bluesy vocalizations, repeating certain phrases for effect, reminded me of how James Blood Ulmer merged skronky jazz with bluesy funk.

Afterward, ELUCID told me this is his first solo tour. I was surprised to hear that: he’s been something of an underground star since his breakout album, 2016’s Save Yourself. However, American concert bookers weren’t interested in the kind of dense, abstract rap he makes…until the COVID era in 2020 (and, undoubtedly, Armand Hammer’s crossover success, especially in the UK). With rap fans stuck at home, he believes, an audience emerged that’s willing to listen closely and patiently absorb his work.

Jean Grae’s In My Remaining Years

I’d like to add some additional comments about Jean Grae’s new essay collection. I hesitated to mention it in my Wire essay because she has frequently complained about male rap dudes that show up on her social media, begging her to make another rap album, and won’t allow her to leave her old identity behind.

In some ways, this is understandable – Jean Grae was truly one of the best of her era. I interviewed her and watched her perform multiple times times, including an opening set for The Roots where she controlled the crowd with incredible precision and grace.

However, she isn’t that artist anymore. She’s now a humorist who writes quirkily about her extraordinary life – growing up as the daughter of South African jazz musicians who emigrated to the U.S., touring the world, finding common ground with sketch comedians in New York, writing one-woman plays (2019’s Jeanius), making visual art canvases to flip online, and even recording a series of self-help affirmations that she characterizes as almost inspiring a cult. In My Remaining Years also explores menopausal changes, her two wrecked marriages, the death of her mother Sathima Bea Benjamin (who played with Duke Ellington), and her realization that she doesn’t quite fit on the gender binary. It’s all rendered in a cheeky and whimsical style that feels very conversational.

I’ll always have memories of the old Jean Grae who dazzled me when she rapped, “I…drop…my…styles like this” on Natural Resource’s “Bum Deal.” But this new Jean Grae is intriguingly different. As a lover and supporter of art, the best thing I can do is set aside the past and absorb who she is now.

Routinely saying what needs to be said. Your historical perspective is invaluable to the underground.