Cutting Room Jams: Feel the Love

New reviews of 21 Savage and Kid Cudi, new pickups, and a few thoughts on Pitchfork.

It’s been nearly a month since I’ve emailed a installment of this newsletter. For those of you wondering, yes, Cutting Room Jams is still active. My absence was due to personal matters: I started new projects and ended my participation in old ones. I was so busy that I barely had time to write. If that seems purposely vague, well, it’s meant to be. I don’t offer everything in my life for online perusal.

At any rate, I’m back and eager to share a few things with you.

21 Savage and Kid Cudi

On January 13, Rolling Stone published my review of 21 Savage’s American Dream. “By now, it’s clear that there’s a stark difference between 21 Savage the wealthy musician, father of three children, and humanitarian known for his charitable works; and 21 Savage the avatar, whose deadpan boasts about murdering rivals, stunting on X bitches, and bullying snitches has thrilled listeners for nearly a decade,” I wrote. “Part of 21 Savage’s appeal is that he’s a confident performer who, for the most part, doesn’t feel it’s necessary to justify why he inhabits a role that has little relation to his current life.”

On January 17, RS published my review of Kid Cudi’s Insano. I wrote, “While music critics have long fussed over Cudi’s work — a fraught dynamic he complained about in the 2021 documentary A Man Named Scott: The Kid Cudi Story — the 39-year-old has become an elder statesman to an audience accustomed to experiencing rap as a vibe-y blur of singsong melodies, inebriated euphoria, and youthful angst.”

Incidentally, I’m one of those critics who “have long fussed” over Kid Cudi. In 2009, I interviewed him for the San Francisco Bay Guardian. I lived in Sacramento at the time, so I didn’t retrieve a print copy of the newspaper. Here’s how it looked online at the time.

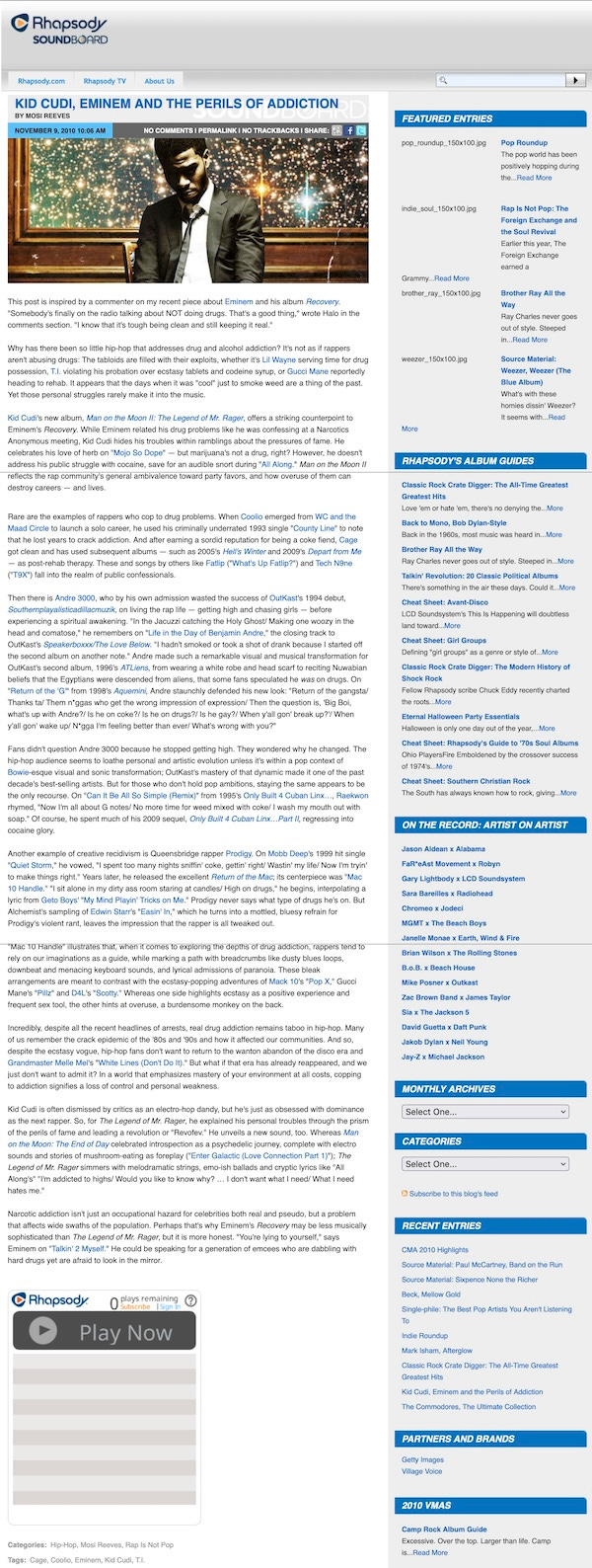

In 2010, I wrote about Cudi’s second album Man on the Moon II: The Legend of Mr. Rager for Rhapsody. I didn’t make PDF copies of my Rhapsody pieces, which turned out to be a very poor decision: The blog no longer exists. Most of my articles were vaporized in the process.

Here’s an essay, “Kid Cudi, Eminem and the Perils of Addiction,” that Rhapsody timed around the release of Man on the Moon II: The Legend of Mr. Rager. I used the opportunity to survey examples of substance abuse in rap music.

Other Cudi albums I reviewed for Rhapsody (which later merged with Napster) include 2012’s WZRD, 2014’s Satellite Flight: The Journey to Mother Moon, and 2015’s Speedin’ Bullet to Heaven. As mentioned before, they’ve seemingly disappeared from the internet.

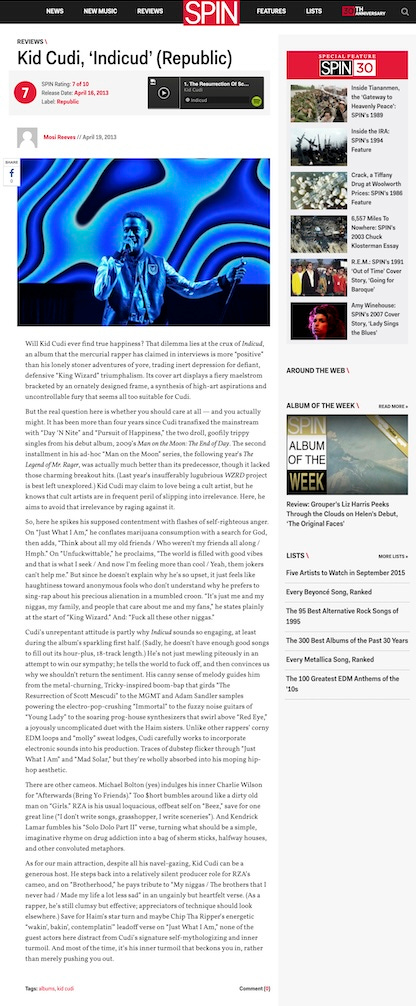

In 2013, I reviewed Cudi’s Indicud for Spin. Much like Rhapsody, I didn’t make a PDF of the original post. The below post is from a 2015 site redesign.

Finally, I reviewed Kid Cudi and Kanye West’s joint album as Kids See Ghosts for RS. It was included in my monthly round-up column of new rap for the site’s short-lived vertical, RS Hip-Hop.

Unfortunately, the site had just hired a new editor who didn’t care for my work. After he decided not to publish the column — even though he had earlier asked me to finish it — I stopped getting assignments altogether. (Shout out to Christopher Weingarten, who originally brought me to RS and tried to advocate for me when the unnamed editor froze me out.) I didn’t become active on RS again until two years later, after that person left the magazine.

Here’s my unpublished review.

You’d be forgiven for assuming the worst from Kid Cudi’s album with Kanye West: The former hasn’t made a decent project since 2013’s Indicud, and West has…well…no need to explain. Yet this The Sixth Sense-inspired title may come closer than any other installment in West’s Wyoming series to realizing his unstated vision of collaborative, empathetic, and emotionally childlike hip-hop music. On tracks like “Feel the Love” and “Reborn,” you can hear the pair embracing the bipolar expressions of love and anger that underline their widely reported struggles with mental illness. Guest vocals from Yasiin Bey and Pusha T float in and out, and there are android gospel flourishes on “Freeee (Ghost Town, Pt. 2)” that extend for a few seconds too long, straddling the line between inspiration and self-indulgence. But the duo’s engagement—and Cudi in particular—is palpable. Their presence is so energizing that the album’s lack of memorable verses is irrelevant. Just the sound of West and Cudi shouting at the heavens is moving enough.

Pitchfork

As indicated with that former RS editor, I’ve had the misfortune of dealing with several inconsiderate editors and writers. Sometimes, their unpleasantness resulted from some legitimate failing, whether that was substandard copy or not meeting deadlines. Just as often, they simply held personal animus or didn’t think I belonged in their publication. Much like the industry it aims to cover, music journalism can be very cliquish and driven by facile traits, where you live, or even which university you attended.

I consider myself a survivor because, in spite all of my flaws, I’ve managed to scrap and climb towards increasingly prestigious publications throughout my peripatetic career. I don’t want to give details away just yet, but I can tentatively confirm that those opportunities have already begun to emerge this year. And yes, I’ve enjoyed the delicious irony of watching someone who disparaged me turn around and try to befriend me on social media, or ask for a favor via email or in person. I don’t hold grudges. I also don’t forget.

These memories are why I’ve had trouble sorting out my feelings about Pitchfork’s sudden disruption, which most observers have predicted will lead to its demise or, to deploy a trendy word, “enshittification.”

Historically, Pitchfork has a complicated legacy, one not necessarily reflected by the many tributes that emerged last month. In fact, as news broke that Condé Nast had laid off much of the site’s staff and planned to merge it with GQ magazine; I was finishing the fourth season of Open Mike Eagle’s What Had Happened Was, which focuses on Questlove’s ‘90s heyday with The Roots. Episode 13, “What Is a Soulquarian?” talks about the rise and the fall of the Soulquarians movement as well as the mixed critical response towards The Roots’ 2004 album, The Tipping Point.

Questlove: We caught a lot of shots for The Tipping Point. Like, our lowest [selling album]…Plus, a new guard had come in. A guard named Pitchfork, with these hip…

Open Mike Eagle: Hip, college educated…

Questlove: …hipster white guys that don’t exactly look like they’re hanging in the neighborhoods of the music that they’re championing. Like, wow, you’re such a cocaine-rap enthusiast. But…

Open Mike Eagle: …but you live in Williamsburg.

Questlove: Yeah! How does that happen and stuff? And I feel like part of ripping down The Roots was burning the emperor’s old clothes. And someone from Pitchfork called it out: The Roots are the people that white people that don’t like hip-hop like.

Pitchfork’s bylines have diversified greatly since the mid-Aughts. (Meanwhile, Questlove hasn’t explained why his own site, Okayplayer, laid off its editorial staff last October.) Yet the notion that Pitchfork is largely staffed with “white hipsters” persists. On Chicago rap duo Angry Blackmen’s new album, The Legend of ABM, Quentin Branch lashes out against the site. “Fuck a publication and them crackers up at Pitchfork,” he raps on “Dead Men Tell No Lies.”

Both claims point to how Pitchfork, as a construct of musical taste, is often presumed to be cast in whiteness, no matter the race or gender of its interlocutors, with a perspective distant from the lived reality of Black and Brown performers. The regime that Condé Nast dismissed, helmed by editor-in-chief Puja Patel, admirably strove to dismantle those perceptions. It’s tragic that they’ll no longer continue their work.

My personal experience with Pitchfork is complicated, but not for the aforementioned reasons. (I don’t feel like getting into it. For now, you can read this BrooklynVegan news story about my ill-fated review of Talib Kweli’s 2016 album Indie 5000.) Its editors and writers were kind and considerate, the polar opposite of the snobby-ass scenesters I occasionally encounter in pop media.

I am forever grateful to Jill Maples for giving me the opportunity to write a few deeply researched stories. Being edited by Clover Hope was an instructive and revelatory experience. I also want to thank Jayson Greene for originally inviting me to write for Pitchfork. Although my first run went sideways, I wouldn’t have found redemption without the staff’s subsequent generosity.

Over the past two weeks, I’ve struggled to negotiate two distinct ideas circulating in my head. I think it’s important to critique Pitchfork’s unique and perhaps unrivaled place in 21st-century music journalism. But as someone who has benefited from its presence, I may be too close emotionally to its still-unfolding story.

Perhaps all I can offer is my own example. I’m someone who weathered over two decades of wounds, many self-inflicted, leaving my dream of being a full-time writer seemingly out of reach for now. During that time, newspapers have bankrupted, magazines have been bought and liquidated, and websites have seemingly vanished into thin air. Yet life begins and ends on its own timetable, separate from commerce and the predations of free-market capitalists. It’s my saving grace.

New Pickups

Let’s end this session on a less existential note. Here’s a few items I’ve recently bought.

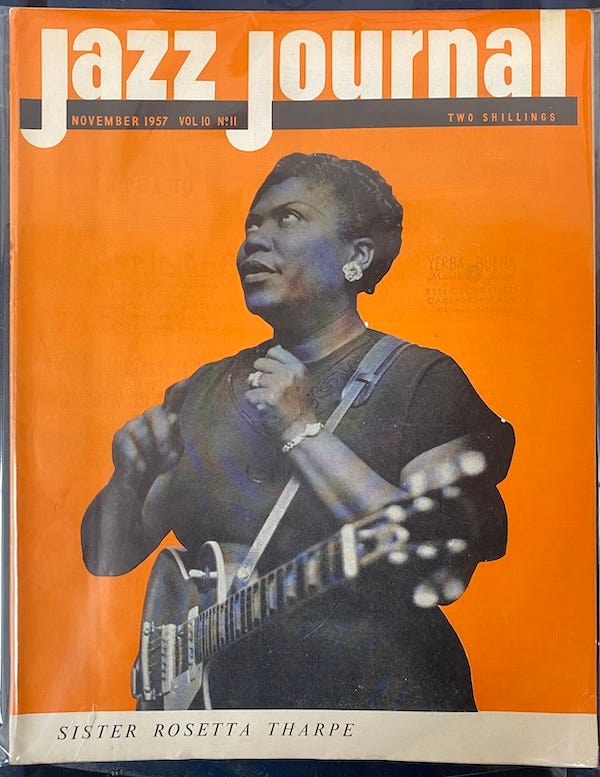

Jazz Journal is a British magazine that profiled gospel musician and rock ‘n’ roll pioneer Sister Rosetta Tharpe in advance of her November-December 1957 tour. Dixieland traditionalists Chris Barber’s Jazz Band opened her dates.

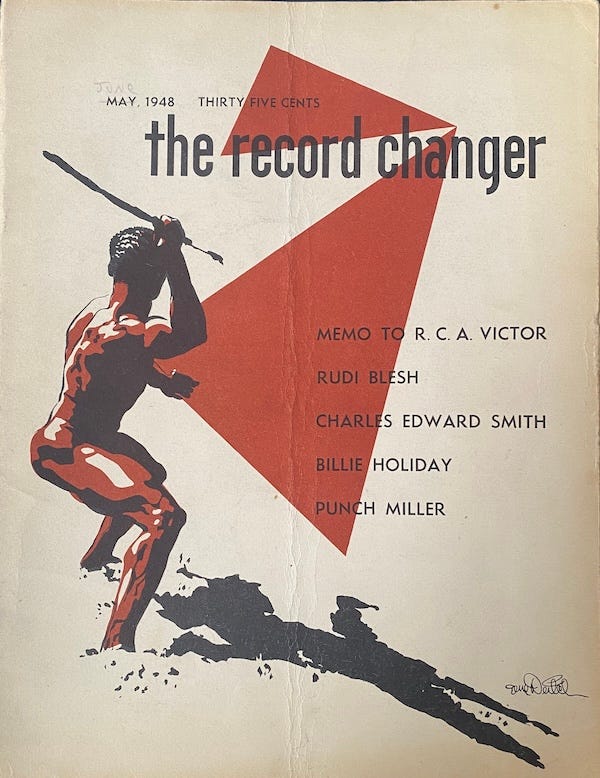

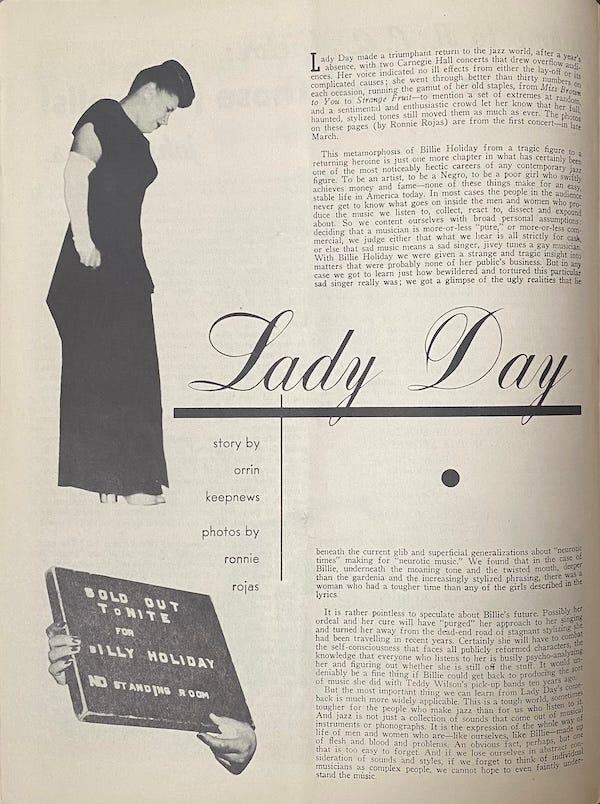

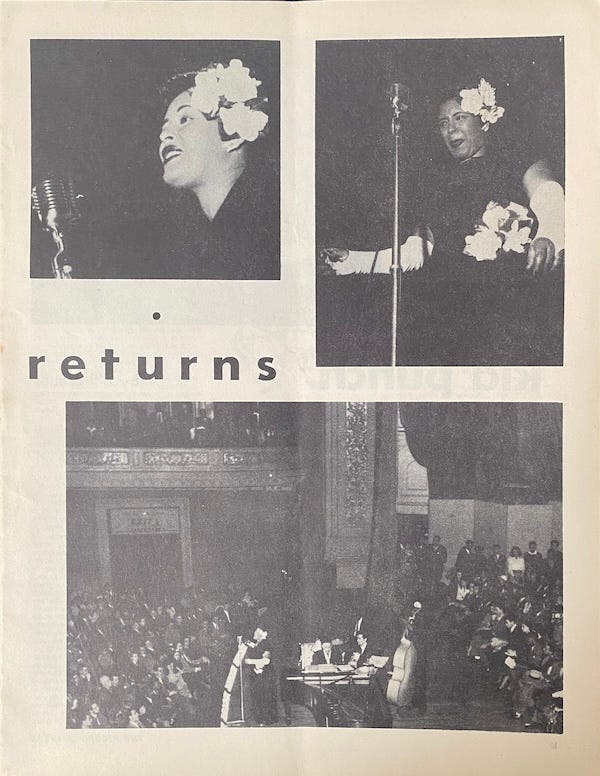

The June 1948 issue of The Record Changer includes a concert review of Billie Holiday’s famous March 27, 1948 comeback concert at Carnegie Hall. (Note the cover date is misprinted as “May 1948.”)

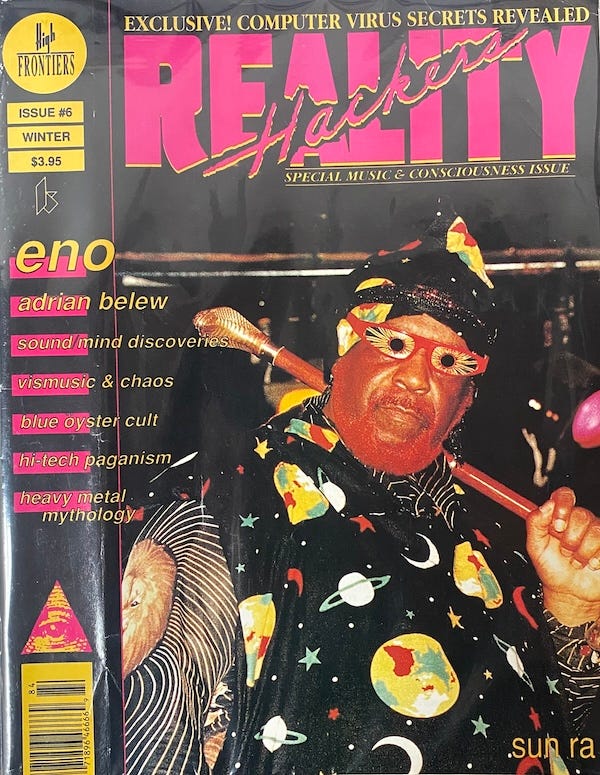

Here’s a Reality Hackers cover featuring Sun Ra. The Winter 1988 issue of the Berkeley-based magazine features a Q&A with Sun Ra conducted by Ira Steingroot prior to his 1987 benefit for Koncepts Cultural Gallery at Kaiser Convention Center in Oakland.

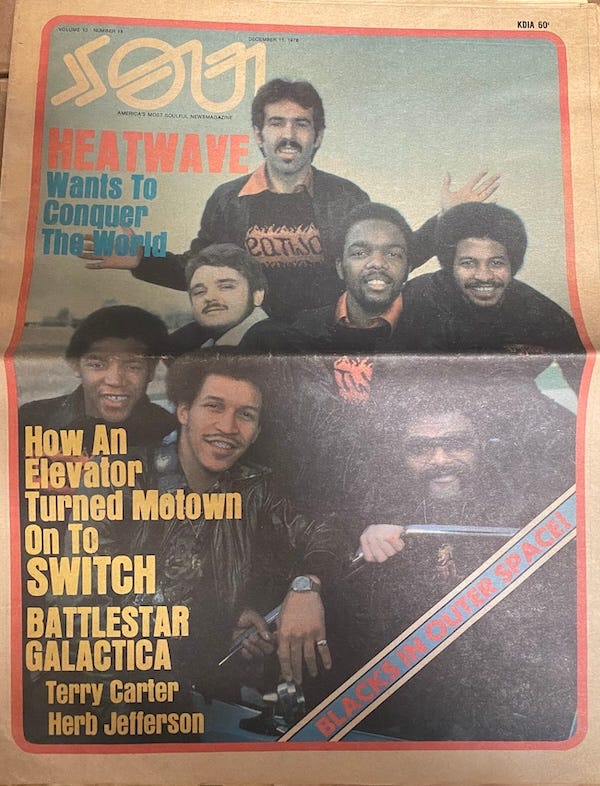

This issue of SOUL magazine features British soul-disco band Heatwave. Inside, singer Johnny Wilder and guitarist Roy Carter are interviewed by Anthony P. Carter.

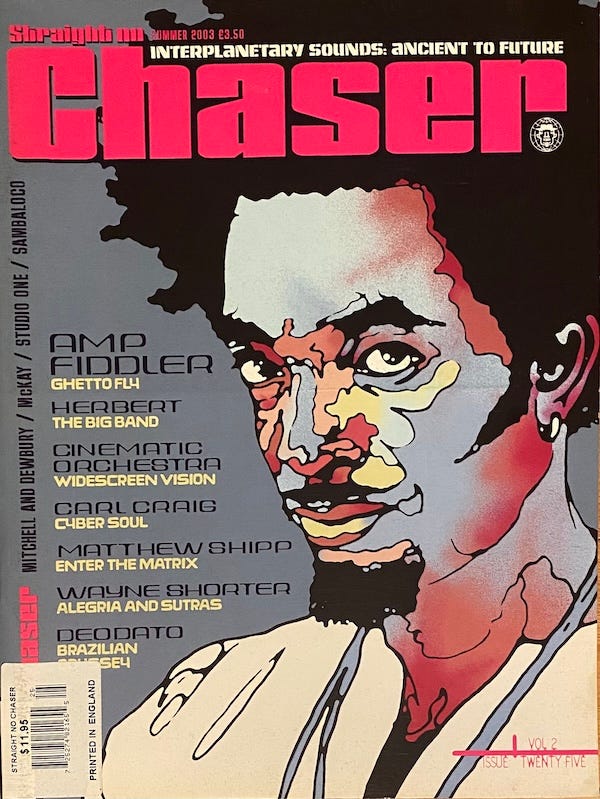

Finally, a bonus: I bought this issue of Straight No Chaser when it dropped in 2003. Rest in peace to Amp Fiddler.