The year is finally drawing to a close, and I’m sending this out in the nick of time, the unfortunate result of being unable to filter my thoughts. Culturally, socially, and politically, this year has been more eventful than most. But I don’t want to trauma-dump everything I witnessed and experienced. Instead, I want to turn to an essay I wrote earlier this year for the 1994 edition of my ongoing “Best Rap Singles” project.

The end of 1994 brought Common’s elegy, “I Used to Love H.E.R.” Many listeners took it as a broadside at the West Coast, an interpretation that Ice Cube encouraged in 1995 on his “Westside Slaughtahouse” single with Mack 10 and WC. But Common’s words sounded more like a protest over the dominant hardcore aesthetic. “I Used to Love H.E.R.” may seem like a haplessly middlebrow sentiment that doesn’t appreciate how vibrant and diverse the music had grown. But as rap reached saturation point, the genre lost its sense of playful innocence, and its ability to create intellectually curious art without profanity or cynicism. Those qualities now seem forever lost.

1994 was 30 years ago. Most listeners don’t have any sense of rap culture before it circulated around profane tales of street activity and lascivious descriptions of sex and wealth-building. To put it more precisely, most rap fans don’t remember a time when rap projects didn’t have “dirty” words.

What happens when societies coarsen, embrace corruption, and begin to treat human interaction as a means to a capitalist end? We trade our sense of ethics and morality for what we perceive as refreshing honesty. Naked lust, self-absorption, manipulation and abuse: Now, we can see ourselves as we truly are.

Rap culture, like all cultures, is a microcosm and an artistic exaggeration of societal forces at work. When Cash Cobain makes “sexy drill” songs about “choking and fucking” his lovers, he’s reflecting the ethos of modern-day pornography. When Drake claims that Kendrick Lamar abuses his partner, and Lamar retorts that Drake preys on young girls, they’re replicating the most damaging social-media accusations – an allegation that someone has (sexually) assaulted someone else – in order to accrue cultural capital. And when rap fans use the details of Sean “Puffy” Combs’ arrest, indictment, and lawsuits to crack off “no homo” jokes, they’re mirroring how we think of femininity and queerness as disgusting aberrations, qualities to be controlled or stamped out of mainstream society.

It’s raw stuff. Part of how rap fans earn credibility, so to speak, is how deep we can wade into the muck, not only by navigating the hundreds of projects that emerge each year, but also by learning to breathe through the shit and pestilence that reflects these Dante-esque descents into human lust and squalor. When AKAI SOLO raps, “Smoking pack in a park/Post-dark free thought/Cause on nights like these/The wind is a tease/The crib is a cage,” he unburdens a mind destabilized by life’s concerns. When we wade through the mud, it makes these moments of clarity feel all the more fleeting and precious.

Still, I can’t help but wonder if there’s easier ways to unburden ourselves. I know the joyously child-like and innocently fresh moments of Newcleus’s “Jam on It” and Run-D.M.C.’s “Rock Box” are long gone, as ancient to us now as a bop by The Mills Brothers or Louis Jordan. And I realize that the likes of Tyler, the Creator and Tierra Whack hearken to that earlier sense of play, albeit by using modern and post-adolescent forms and themes. But memories of the genre’s past can not only help us document what has been lost, but also help us revive ways of building and creating better futures.

2024 Rewind

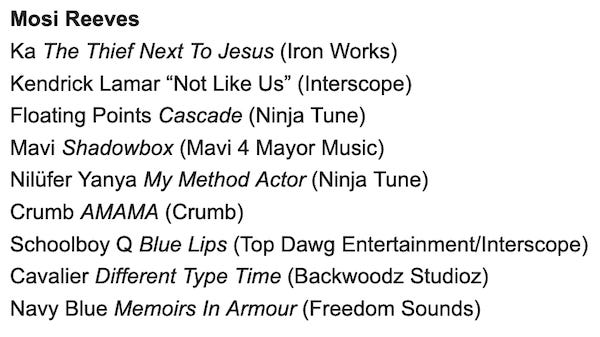

Unlike last year, I only participated in two year-end exercises this year, one for The Wire’s January/February 2025 issue and Uproxx. (The Uproxx poll won’t be published until early January.) Here’s my top 10 picks for the former.

Note that the editors inexplicably left off my vote for SZA’s “Saturn,” so there’s only nine picks on my list.

Here’s what I submitted for the magazine’s annual “Critics’ Reflections” section.

A Tribute to KA

I want to close by offering my Rolling Stone homage to Kaseem “KA” Ryan, a Brooklyn rapper who passed away on October 12, 2024. For those who haven’t heard of him, KA was an exceptional lyricist and producer who valued hip-hop as a form of uncompromising Black self-expression. He was the musical equivalent of Haile Gerima and Chris Marker, a true theorist who used concepts to explore a life of yearning and intellectual inquiry. There are others in rap who create art with similar ethics – Baltimore artist Labtekwon, whose work I’ve revisited recently, as well as Myka Nine from Freestyle Fellowship come to mind. In terms of quality, however, KA truly stands alone.

One of my favorite writing moments this year involved hearing the news of KA’s death on Sunday; realizing that I had to honor his work in some way; emailing my RS editor while at work on Monday; then spending Monday evening furiously composing a tribute and sending it off for postig on Tuesday. RIP tributes are aspects of journalism that often feels macabre and perfunctory, like throwing up a hasty hashtag post for social media likes. How can you sum a life’s work in a day or two, much less a few hours? Still, after having to suspend or cancel so many projects this year because I simply didn’t have time, I felt pride at realizing my intentions for once, if only for a short 1200-word article.

There were, of course, many brilliant musicians adjacent to the hip-hop space who passed away this year, from Saafir (who I wrote about earlier) to early influences such as Quincy Jones (who co-founded Vibe magazine), Nikki Giovanni (who collaborated with Blackalicious), and Gylan Kain of The Last Poets.

RS is behind a paywall, so I’m posting my KA essay here.

Ka Was the Visionary Soul of Underground New York Hip-Hop

Kaseem “Ka” Ryan, who passed away on Oct. 12 at the age of 52, was a one-of-one hip-hop visionary who left a legacy as brilliantly idiosyncratic as any the genre has produced. He emerged as a fiercely evocative artist in a moment when a new wave of voices revitalized street rap, shearing the style from its mid-Nineties thug origins while avoiding any pretense of commercial viability, and girding it with dusty, deeply-sourced sample loops. Ka’s 2012 album, Grief Pedigree, is widely cited alongside Roc Marciano’s 2010 album, Marcberg, as a blueprint for an entire subculture of vocalists spitting world-weary, metaphorical verses about the hustle game, its triumphs, and its setbacks. (The late Prodigy’s 2007 collaboration with the Alchemist, Return of the Mack, as well as the late Sean Price’s 2005 album Monkey Barz deserve mention as important precedents.) Boldy James, Westside Gunn, Conway the Machine, Benny the Butcher, Rome Streetz, and Tha God Fahim all built on, added twists to, and created new lanes out of the cultural mood that Ka captured.

Yet while Ka was representative of a style, he was also unique, as so many fans who flocked to social media to express their heartbreak and appreciation for him said. With 2013’s The Night’s Gambit, the rapper-producer from Brownsville, Brooklyn, reduced his sound to wisps of melody and spare, minimal percussion. The effect made his hushed, crackly voice feel like a wood-carving tool shaving images into sepulchral mists. His friend Marciano — the two frequently appeared on each other’s work and even promised a joint album that has yet to see light — crafted a similarly “drumless” sound with his 2012 high watermark, Reloaded. But while Marciano filled his tracks with bleakly vivid musings of a criminal mastermind, Ka infused his music with memories of previous exploits, past and present friends, regrets over paths he had chosen, and hope for the life he could still lead. It felt like “grown-man rap” of an exemplary sort, not concerned with the meanderings of middle-age complacency, but the reckoning that comes after years of human survival. He reached uncommon depths of personal insight. “Me and Roc always said, when Ka rapped it was like he was delivering his words from the top of a mountain off a stone tablet,” wrote the Alchemist on X.

Like many of his peers in this milieu, Ka was once an also-ran in the hypercompetitive rap industry. He came of age in the Eighties crack era, as he told Red Bull Music Academy in 2016: “Put like this, my cousins were selling drugs, my aunt was on drugs, my cousin was selling drugs, his sister was on drugs, his brother was on drugs.” He sold drugs, too, while filling notebooks with his rhymes, inspired by the likes of Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message.” By the Nineties, he was making demos and linking up with Natural Elements, a sprawling collective of MCs who briefly made noise in the New York underground. When a subsequent project called Nightbreed faltered — despite their standout 1998 12-inch single, “2 Roads Out the Ghetto” — Ka joined the New York Fire Department, eventually rising to a rank of captain. He was one of the first responders during the 9/11 attack on the World Trade Center.

Ka’s self-released 2008 CD, Iron Works, coincided with the underground’s shift from an “independent as fuck” protest to a working-class demimonde. Some had never quite cracked the mainstream, despite modest acclaim from rap-heads and college-radio spins. Others had navigated major-label politics, with mixed success, and could still command a substantial audience. GZA from Wu-Tang Clan, years removed from his 1995 platinum-certified classic, Liquid Swords, belonged in the latter category. After hearing Iron Works, he invited Ka (as well as Marciano) to cameo on 2008’s Pro Tools, giving the rapper a well-earned moment of validation.

As Ka formed a discography during the last decade or so of his life, he wrapped his projects in overarching concepts: The Night’s Gambit and chess metaphors; 2015’s Days With Dr. Yen Lo’s (made with producer Preservation) unsettled, possibly brainwashed thoughts, à la The Manchurian Candidate; and Japanese codes of integrity in 2016’s Honor Killed the Samurai. “Of [hip-hop], I’m a samurai. I’m holding on to something that’s not treasured anymore: lyrics,” Ka told Rolling Stone.

By 2018’s Orpheus and the Sirens — a collaboration with producer Animoss as Hermit and the Recluse — and 2020’s Descendants of Cain, Ka enjoyed a reputation akin to a Michelin-starred chef. Each new release felt like a gift of richly appointed beauty. “It’s obviously for a more mature audience,” he told Passion of the Weiss in 2015. “If you’re listening half-heartedly, you gonna miss a lot of things. I don’t want you to sit down every time you listen to a Ka record. But if you want to really absorb what I’m saying, you may have to take some time.”

The “lyricism” trope has sometimes been used by fans and artists alike to belittle less-verbose “mumble rappers” who focus on melody, flows, and hooks. Indeed, Ka’s work, in all its conceptual and thematic intensity, could feel like a generational bulwark against rap’s perceived aesthetic decline. But this kind of thinking pays little tribute to an artist whose legacy stands completely on its own, whether in comparison to the Nineties “golden era” or now, when rap feels too complex and diffuse for any one person to grasp.

Fiercely self-contained, Ka sold vinyl and CDs on his website and through select stores across the U.S. and Europe. He filmed YouTube videos to promote album tracks; for Grief Pedigree, he made a video for every cut. He rarely performed concerts, a format that he came to believe was a poor fit for his contemplative raps. Eventually, he didn’t bother shipping out physical product, either. He simply dropped an album, made it a digital exclusive for several days before posting it on streaming services, then held one-day-only pop-up shops in New York to move units and shake hands with supporters. That’s how hundreds of fans, many flying in from out-of-state, showed up at 104 Charlton St. in Manhattan’s Hudson Square on Sept. 28, and lined up in the rain for hours to press flesh with perhaps the finest rap craftsman of his era. It’s unlikely they knew it would be his last public appearance.

Ironically, Ka’s final album, The Thief Next to Jesus, is cloaked in spiritual meditations. He loops up sundry gospel calls and shouts as he navigates a troubled relationship with organized religion and how God sustains him. “When you give much, much is received/If you ain’t livin’ life in crisis, I don’t trust your lead,” he raps on “Tested Testimony,” noting the power of community and how “if one make it, we all do.” And for someone celebrated for his haunting power, “Bread Wine Body Blood” betrays a moment of humor — “Don’t get it twist, I like a pretty miss with a fast gat” — as he warns today’s youth not to “be the weapon they use to harm you.” Heard now, every song feels like an urgent message from someone whose gifts were all too finite.